Installation

Until Ceramic is available from Quicklisp, you have to clone it to your

Quicklisp local-projects directory. Assuming your Quicklisp directory is

~/quicklisp:

git clone https://github.com/ceramic/ceramic.git ~/quicklisp/local-projectsThen, either restart Lisp or run (ql:register-local-projects).

Getting Started

First, we need to load Ceramic. We do this with Quicklisp:

CL-USER> (ql:quickload :ceramic)Ceramic needs to download some things to run, so let's do that:

CL-USER> (ceramic:setup)Now we're all set up. Let's start creating some browser windows. Run the following code:

;; Start the underlying Electron process

(ceramic:start)

;; Create a browser window

(defvar window (ceramic:make-window :url "https://www.google.com/"

:width 800

:height 600))

;; Show it

(ceramic:show window)

An 800-by-600 pixel browser window pointed at Google should pop up.

Building a Desktop Web App

With Ceramic, we can write a web application – using Clack– and create windows that use it.

We'll be using Lucerne, a web framework built on Clack to write the web app, and Ceramic to use it as a desktop app.

First, load Lucerne:

CL-USER> (ql:quickload :lucerne)Then, start the Electron process,

CL-USER> (ceramic:start)Now, let's create a basic application. The source code and system definition of

this app is in the examples/hello-world/ directory of the Ceramic source

code, so you can play around with it.

(in-package :cl-user)

(defpackage ceramic-hello-world

(:use :cl :lucerne)

(:export :run))

(in-package :ceramic-hello-world)

(annot:enable-annot-syntax)

;; Define an application

(defapp app)

;; Route requests to "/" to this function

@route app "/"

(defview hello ()

(respond "Hello, world!"))

(defvar *window* nil)

(defvar *port* 8000)

(defun run ()

(setf *window*

(ceramic:make-window :url (format nil "http://localhost:~D/" *port*)))

(ceramic:show *window*)

(start app :port *port*))

(ceramic:define-entry-point :ceramic-hello-world ()

(run))

Don't worry about that define-entry-point macro, we'll get to that later.

Calling run, a browser window with the text "Hello, world!" should pop up.

Shipping

Ceramic can compile an application -- both produce an executable of the server

and compile all the required resources -- into a bundle, which is basically an

archive file. All you have to do is call the bundle function:

(ceramic:bundle :ceramic-hello-world)

And that's it. Head over to the directory of the hello world example,

examples/hello-world/, you'll see a .tar file with the app's

executable. Extract it and run the app. A window should pop up and you should

see the 'Hello, World!' text.

You can also tell it where to store the bundle through an optional argument:

(ceramic:bundle :ceramic-hello-world :bundle-pathname #p"build/bundle.tar")

More Complex Apps

Of course, a web application isn't just routes, you also have to bundle all sorts of assets. Ceramic takes care of that for you.

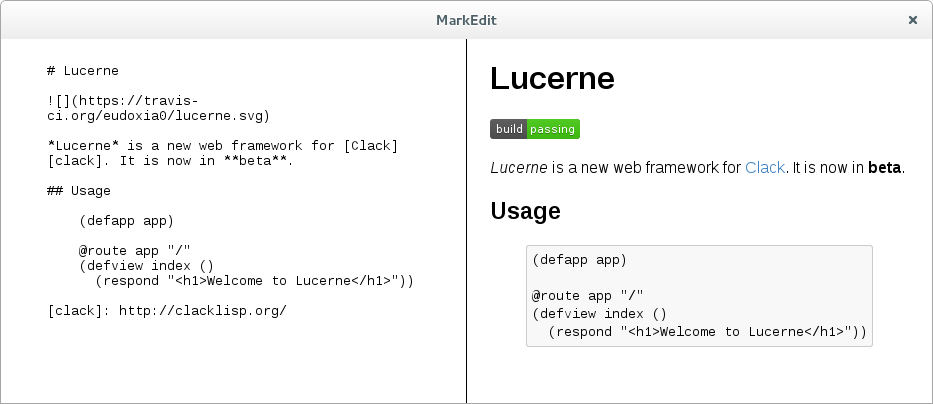

For this example, we'll use

MarkEdit: This is a simple

Markdown editor and previewer. On startup, you get a window with two panes: On

the left pane, you type Markdown code, and on the left, you get the rendered

HTML. You can see it in action below:

To test the app locally, just run (markedit:start-app). To deploy the app, we

run the bundler command:

(ceramic:bundle :markedit)

Extract the app and run it: You'll see the window pop up and you can start editing. Close it and the app shuts down.

The way Ceramic handles resources is by associating tags (such as web-assets

or data-files) to certain pathnames relative to the system's source

directory. In development, you reference a resource tag and get the pathname

to that source directory. When bundling the app, resource directories are

copied, and in production, when you reference a tag, you get the pathname to the

copied directory inside the app's bundle.

If you look at the source of the MarkEdit application, you'll see resources are defined like this:

(define-resources :markedit ()

(assets #p"assets/")

(templates #p"templates/"))

What this means is the tag assets is associated to the assets/ directory

in the directory of the :markedit system, and the templates tag is

associated to the templates/ directory. You can associate tags to

directories at any depth.

We the resource-directory function to get the directory associated to a

tag. In MarkEdit we use this to set the directory where templates are stored so

Djula can access them:

(djula:add-template-directory

(resource-directory 'templates))

(defparameter +index+

(djula:compile-template* "index.html"))

A useful function – to prevent you from calling merge-pathnames all

the time – is the resource function: This takes a tag and a

pathname, and is the equivalent of adding that pathname to the end of the

directory associated to that tag:

(resource 'assets #p"css/style.css")

;; is the same as

(merge-pathnames #p"css/style.css"

(resource-directory 'assets))